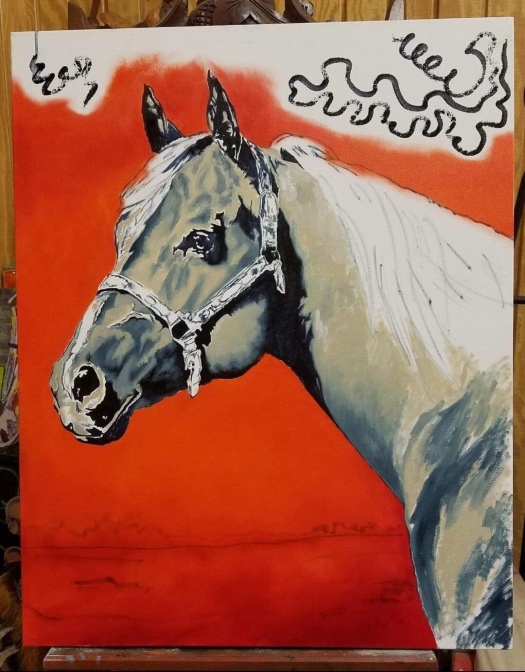

A few weeks ago my friend, Angela Festervan shared with the Facebook world a picture of a painting she had been working on. It was a portrait of a horse and it was absolutely stunning. Every once in a while Angela shares progress pictures of paintings that she is working on and I just live for them.

There aren’t many artists out there brave enough to reveal bits of their process with the public. I have to imagine it’s kind of like baring your soul in some way. It’s not the finished product so it’s a bit more raw and unrefined. It might even invite judgement by untrained eyes or just your average Facebook trolls.

In so many ways, training horses is like an art form.

I have always explained the concept of putting a foundation on a horse like putting up the foundation and framework of a house. But the longer I have trained horses the less I like that metaphor.

When constructing a house there are concrete methods and plans that give a consistent and predictable result. With horses, and with art, there are so many variables that come into play.

Horses are not like houses. They are living breathing masterpieces just waiting for an artist skilled and patient enough to bring them to their potential.

I reached out to Angela last week and asked her about her art work and if she saw the comparison between training horses and creating art.

Angela also trains phenomenal barrel Futurity horses and starts colts so she was the perfect person to weigh in on this. Here is what she had to say.

“Selecting the right canvas, paint, subject, and composition are the same as selecting a prospect. You have to start with the best at your disposal.

Taking the time out to study with a professional painter and hone your skills of HOW to paint will determine your success with a painting just as taking the time out of your life to study with a professional trainer and hone your skills of HOW to train will determine your success with a prospect.

Give me a canvas, brushes, and paint today and I can produce a work of art. Give those exact tools to me before I studied and I would have created a disaster.

I always had the drive and desire to paint but the skill had to be learned. I didn’t get here all by myself with no guidance or direction.

Great trainers aren’t built all by themselves in their own backyard. Even eagles with feathers and wings flop around on the ground while their parents teach them to fly.

So after skill is collected and equipment is laid out, it’s time to apply those lessons.

You have to have an outline, a sketch, just some lines and parameters to keep the focus. You have to step back from the canvas, give it space and observe “is it ready for the first steps

of paint?” Be honest, don’t rush it. Sleep on it. Sleep on it again.

That’s the first stages of groundwork. Building a relationship or a conversation with the colt. Don’t rush into starting the colt. If you think he’s ready, sleep on it. Do more groundwork. Sleep on it again. You can’t “think” he’s ready, you have to KNOW that he’s ready.

When you know that your sketch and placement of composition on the canvas is as correct as possible then you’re ready and it’s ready. Every work of art is different, some are ready the 1st day, some may take weeks. Don’t rush. Take the darkest shadows and block them in, you’ll work into the light. Make sure you have time because this step is the first ride and you do not get to place a time frame on the first ride. You ride until the colt is comfortable.

You must be confident. Art and horses smell fear and neither art nor horses are well managed by a fearful painter or rider. Be brave and relax.

Give the painting a few days to dry just as it is, don’t work anything new onto it. Same with the colt, you aren’t trying to teach the colt to sidepass yet. You just want him to get confident and comfortable carrying a rider who is throwing him off balance. He is still afraid even when he doesn’t show it. Don’t take advantage of his gentle nature. Appreciate his gentle nature.

Now for layers. You apply a layer of paint. This might take days to build. You apply a layer of education to your colt, this may take weeks. These are light, thin layers. Very light, very thin. Your detail is blurry and hardly recognizable. Your hands are light with the colt. Apply his education in thin layers.

He’s not supposed to be slamming himself into a sliding stop or spinning like a seasoned reiner. You are thinly apying a left turn, a right turn, a few steps backing up, an easy whoa. Nothing dramatic or impressive. Just the blurred outline of a trained horse. Just ideas of value and shape.

It’s so important to allow one layer to dry before applying another layer. If you layer red, let it dry, layer yellow, let it dry, and then layer blue you’ll get a gorgeous and natural blood bay horse. If you layer too fast without allowing each foundation to set in then you will get poopoo greenish, purple, grey mud on a ruined canvas.

Layer your colt’s lessons the same. Rushing will cause confusion and a ruined mind.

Holy shit, it’s time to exit the round pen! So by now you’ve got a lot of time and money and talent invested in this painting. Good canvas, good paint, and good brushes aren’t cheap. You’re also pretty damn proud of how your work appears and screwing it up could mean tossing the canvas into the trash and losing all that time and money.

Exiting the round pen to early could mean using your colt’s light mouth to save yourself. You could get hurt. You could die.

You need to KNOW it’s time. You need to be confident. Your colt is going to be scared and you have to remain calm even when you think you may die. Let mistakes happen and don’t try to force fix a mistake, you can paint over them when they dry as long as you don’t freak out. Let your colt spook or trot or lope out of collection through the fields. Don’t try to force him to interact with scary objects. Don’t punish him for being afraid. Don’t try to force him into collection, you stand up in those stirrups if you can’t sit the camter. After this layer of training is dry you can add the details of equitation.

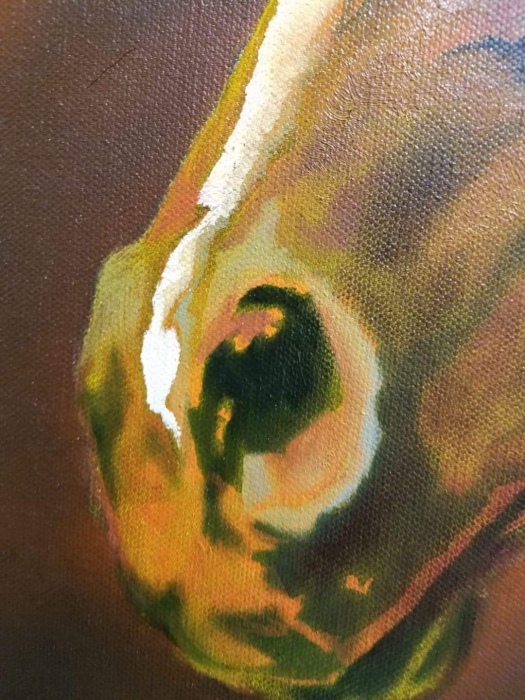

The details. Details in a painting are important, the highlight in an eye, the placement of the nostril shadow. Details in the horse are equally important, the turn on the hauches, the leg yield must be pure. DON’T OVERDO THEM. From a distance a well executed painting will appear to have had every single hair brushed in, from a distance a well trained colt appears to do every little thing that the rider asks. Now get up close. The “idea” of hair is “suggested” not gruelly forced. The viewer is set up to see a 3 dimensional image on a 2 dimensional surface. Just like the painting, simply set your colts up to perform.

Don’t hold reins tight and spur him into a left lead, instead, simply apply a little leg. Sink a little weight over the right hind and feel as he easily shifts into a left lead. If he takes the right lead then go right, play it off and act like that’s what you asked. From a distance, the audience will never know the difference. Layers. Building layers.

Spoken like a true artist and a true horsewoman. Thank you, Angela for sharing your insight with me and inspiring me to find the beauty in artfully developing the horses I have the opportunity to train.

I loved this comparison so much. Such a beautiful way to describe the process.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Cassie!!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for sharing this process with the world! I love your journalism! See you at the shows soon!

LikeLiked by 1 person